Did you know that the namesake of the Cheat Mountain Salamander excursion train is found only in West Virginia? This rare critter is found in Grant, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Randolph, and Tucker counties and is one of the few vertebrate species unique to the Mountain State. The Cheat Mountain salamander’s tail is shorter than the length of its body and head, which helps distinguish it from other small woodland salamander species. It has been on the federal threatened species list since 1989 due to loss of red spruce forests that make up its habitat.

Cheat Mountain (once the largest red spruce forest south of the Adirondacks) was extensively logged in the early twentieth-century for its highly prized timber, which was even used in the construction of world-famous Martin guitars in the 1930s. The Cheat Mountain Salamander excursion train travels all the way to the former logging camp of Old Spruce.

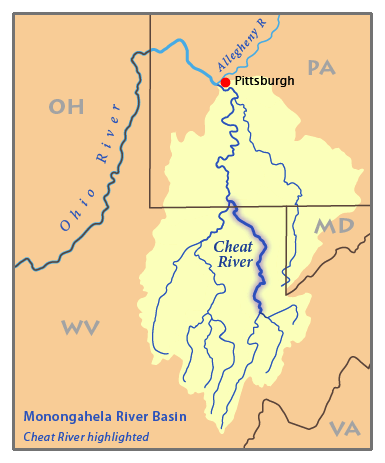

Both the Cheat Mountain Salamander and the New Tygart Flyer trains follow the tracks along the banks of Shavers Fork River, which is one of the forks of the Cheat River. Did you know that there is a traditional fiddle tune called “Three Forks of Cheat” that is known throughout the country, and even in other countries, thanks to a family of West Virginians?

This folk song (listen below) is most commonly associated with the Hammons Family from Pocahontas County, a multi-generational line of musicians who helped pass on some the best-known traditional songs from West Virginia. The Hammonses were unique because they played fiddle and banjo as solo instruments and not in the string band ensembles that had become common elsewhere throughout Appalachia. Edden “Ed” Hammons was the first to be recorded and was highly regarded as one of the best fiddlers in the area. “Three Forks of Cheat” is often associated with Burl Hammons, who in the early 70s was recorded by folklorists Alan Jabbour and Pocahontas county native Dwight Diller. Burl learned the song from his uncle Peter, who along with his uncle Edden represented a fast-disappearing nineteenth-century way of life that placed great importance on rivers and waterways as local landmarks, means of travel, and keys to livelihoods. Burl Hammons remembered how important rivers were to his grandfather’s generation:

“And, uh, they knowed all the rivers, where they’d go in at, where they headed in, that’s the way they’d travel, by the rivers and stuff, by the creeks. …So now that’s the way them fellers lived. Of course they had cows now and stuff, they had a cow from home cause that’s the only way they had to make their living boys, now there’s no other way of making a living now. Eventually at last they, they got to building these splash dams and they was a company come in there and went to buying- ah- these poplar timber. And down here in the Little Fork, Grand-paw Hammons, he took a job in there, a-getting that poplar timber out. Well, they had a, they – well, they had a horse or two but then they, they peeled that poplar. They peeled it and then run it off down to the, to the creek, run it, get it down to the creek. And then they’d get a whole big jam of logs in there and then turn that dam loose. And then they’d go and they’d take ’em to the, went to the mill. And that’s how they got ’em to the mill.”

The Cheat was so important for travel that in 1870 it was declared a public highway. The Cheat and Shavers Fork were used by W. S. Dewing and Sons to float timber to be milled until they established a sawmill and Cass and the railroad became the primary means of moving the wood. The Hammonses played other songs about local rivers like “Cranberry Rock”.

Southern American fiddling is unique in its large number of song names that celebrate rivers and waterways, which reflects their importance for frontier settlement and travel. Examples of banjo and fiddle songs played throughout the Southern Appalachians include “Cripple Creek”, “Mississippi Sawyer”, “Forked Deer”, and “Boatin’ Up Sandy”. There are many such songs related to rivers just from West Virginia including “Wading the Cheat”, “West Fork Gals”, “Three Forks of Reedy”, and “Hell on the Blackwater”. Nowadays the Cheat River is said to have five forks- the Blackwater River and Dry, Laurel, Glady, and Shavers- so why does the song only refer to three forks? Like any good folk song, its origins are not clear. According to folklorist Gerald Milnes, the old-timers used to refer to Shavers Fork simply as the Cheat River. So a local might name the forks of Cheat as the Glady, Dry, and Laurel. Nevertheless, the Cheat has been immortalized through songs that are played and enjoyed locally and far beyond West Virginia.

Written by Ben Duvall-Irwin

AmeriCorps Member serving at the Elkins Depot Welcome Center

Three Forks of Cheat:

Sources:

Clarkson, Roy B. “Cheat Mountain.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 26 January 2012. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1111

Jabbour, Alan. The Hammons Family. Cambridge, Mass: Rounder Records, 1998.

Julian, Norman “Cheat River.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 28 June 2012. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1122

https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/places-we-protect/west-virginia-cheat-mountain/

Pfly – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1639370

Stihler, Craig W. “Cheat Mountain Salamander.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 29 June 2012. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1117