The history of the Underground Railroad in West Virginia is still something of a mystery even after all these years. A series of safe points from the Deep South leading into Canada, spirituals such as “Follow the Gourd” were integral to guiding enslaved men, women, and children to a life of freedom up north. While certain routes along the Underground Railroad are well-known in the Northern and Eastern Panhandles and along the Ohio River, the heart of the Mountain State has not been examined in great detail.

The Beverly Heritage Center researched the role of the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike, an east-west route from the Shenandoah Valley to the Ohio River finished in 1845, played in the Underground Railroad.

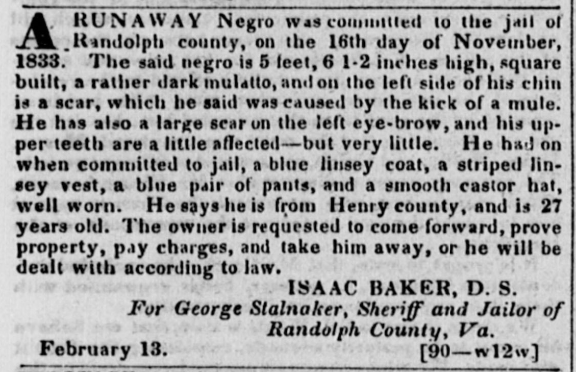

One of the better-known mentions of freedom-seekers in Beverly is a case from 1833, where an unnamed man from Henry County, Virginia, was captured and imprisoned in the 1813 Randolph County Jail. Though he is not mentioned by name there is a full physical description of him, including his height, complexion, and the presence of scars. He would have most likely traveled along the section of the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike between Beverly and Huttonsville – either on his own, or on his way to imprisonment.

It is clear that the Turnpike was used in a few select cases by enslaved people seeking a life of freedom according to an article in the Staunton Spectator from 1853. Three men escaped from Highland County, Virginia and were traced as far as Parkersburg, WV. One of the three had a certificate of freedom, and the three men were allowed to go on into Ohio. The slaveowner pursuing them likely enquired about them at the various tollbooths along the route of the Turnpike. There were tollbooths at Traveler’s Repose, in Pocahontas County, one five miles east of Huttonsville, one at the Henry Suiter House in Beverly, one near Burnt House, and one in Parkersburg which served this Turnpike as well as the Northwestern Turnpike.

Slavery was a fact of life along this road. What is unusual is that rather than using a north-south route, the evidence that the Beverly Heritage Center staff have uncovered indicates that a route west – to the Ohio River – could be used by enslaved people from what is now West Virginia.

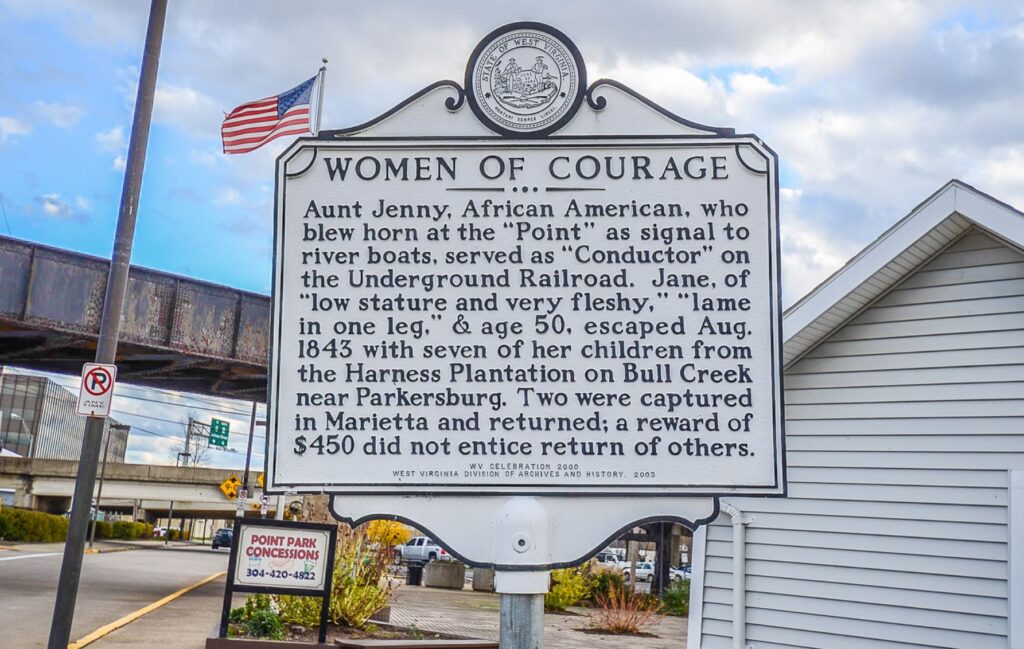

The question remains though how extensive the Underground Railroad’s presence was along the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. While it was a route used by freedom-seekers, there is only concrete evidence for a “safe house” in Parkersburg. There, a free woman of color named “Aunt Jenny” would blow a horn when the passage was safe. Oral history recounts that California House in Wirt County and Burnt House in Ritchie County may have had associations with the Underground Railroad.

The case of Burnt House was quite a tragedy. Two men disappeared at Jack Harris’ Tavern. His son – a mixed-race man named William – was a prime suspect. One of the theories was that the two peddlers who disappeared were agents along the Underground Railroad. An enslaved woman named either Deloris or Delsie was a witness in this affair – she was also rumored to be romantically linked with William Harris. Jack and William Harris left town for Texas, where the latter was supposedly executed by hanging. Deloris then set the tavern ablaze, and witnesses recounted seeing her dance on the second story of the building as it burned to the ground.

Life for enslaved people in West Virginia was incredibly difficult, and it is easy to see why so many chose a dangerous path towards freedom. Last June, the Beverly Heritage Center erected a small display case about the Underground Railroad along the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. Beverly Heritage Center hopes that by researching this history and confronting it head-on, they can present the past in a more inclusive, honest manner.

Article Credit: Dr. Christopher Mielke, Executive Director of the Beverly Heritage Center and Jessica Black, an AmeriCorps Member serving at the Beverly Heritage Center through the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area